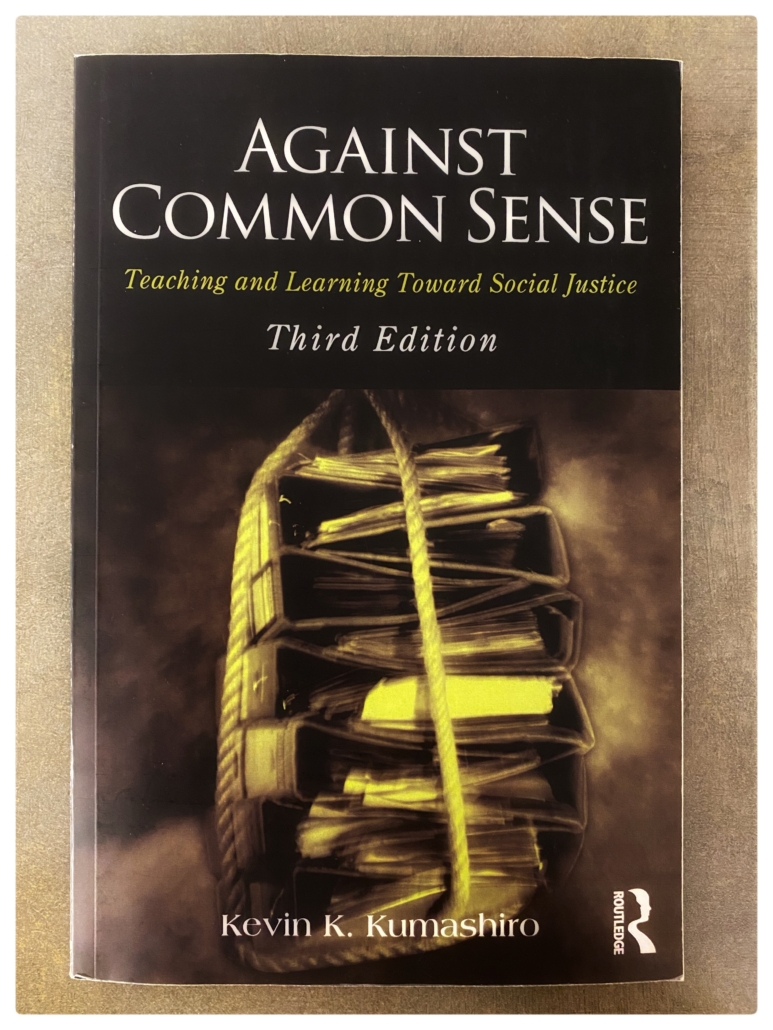

Against Common Sense: Teaching and Learning Toward Social Justice was published in 2004. A second edition was released in 2009. Finally, the third edition (summarized here) was published in 2015. It contains updated resources for further reading and reflection questions at the end of each chapter.

The author is Kevin K. Kumashiro, the former Dean of the School of Education at the University of San Francisco. He has published dozens of articles and essays on education and social justice; and has presented worldwide regarding equity, educational reform, and social justice. Against Common Sense is one of six books he has penned.

In this book, Kumashiro outlines issues in the educational system, specifically with teacher education at the K-12 level. Only particular perspectives are shared because teacher education programs and even educational standards prescribe what knowledge is valued and the acceptable manners of teaching students. This behavior reinforces the values of privileged groups. He introduces the term troubling knowledge, defined as “to complicate knowledge, to make knowledge problematic” and “knowledge that is disruptive, discomforting, and problematic.” (Kumashiro 8-9) He argues that being a “good” teacher is not a lack of knowledge because teaching and research perpetuate oppressive ways. Rather than emphasizing “good” teaching, educators should work towards being “anti-oppressive teachers.”

The book’s first half outlines what anti-oppressive teaching is and how to work towards being an anti-oppressive teacher. The book’s second part examines ways to prepare anti-oppressive teachers in six disciplines: social studies, English literature, music, “foreign” languages, the natural sciences, and mathematics.

Part 1: Movements Towards Anti-Oppressive Teacher Education

An anti-oppressive teacher continually works to become anti-oppressive but never reaches this goal. This is much like an asymptotic line that approaches zero but never reaches it. Since the core of anti-oppressive teaching is to constantly examine the motives, emotions, and implications of a topic – to examine from as many perspectives as possible – there is always more work to do. Engaging in anti-oppressive teaching is a life-long goal.

Based on an understanding of what the author outlines in the text, here are the differences between Traditional (or common sense) teaching and anti-oppressive teaching below:

Traditional Teaching

- Comfortable.

- Covers a set of standards that everyone should know as if that is all there is to learn.

- The student learns the “right things.”

- Looking at what is known and only that

- Outcomes are predictable/known in advance

- Learning often stops once the standard is met

- Accepting what we learn as it is

Anti-Oppressive Teaching

- Uncomfortable

- Challenges the partial nature of the student/school’s knowledge

- Learned what matters to school/society and critically examined the what, why, and how it is learned

- Looking beyond what is known

- Outcomes are not predictable

- Creates a desire to do more work

- Challenging the larger social context

This type of learning (and teaching) is challenging. It is uncomfortable for a person to learn they have incorrectly done a process, that their understanding of themes in a story did not consider gender discrimination, or that their knowledge of a society issue negates the needs of an entire segment of the population. Humans do not like to learn that they are wrong or to have their worldview challenged. This situation can cause a learner to enter a state of crisis, which causes emotional distress and asks for change on the part of the learner. In order to work through a crisis, students need support. They are less likely to learn from the experience and change from it without this support. A student who is not supported could resist changing and become even more resistant to adjusting their view on the situation.

For example, I have been reading a lot on racism in our society and recently finished Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism by James W. Loewen. In this book, the author outlines how towns, cities, and suburbs across the U.S. have systematically kept out non-white populations, such as black, Chinese, and Latinx people, since the late 1800s. White people kept people of color out of communities through violence, discriminatory laws, and restrictive covenants on properties in these communities. I discovered that the county I grew up in, Osage County, Missouri, was likely sundown and purposefully kept black people from settling there. This information challenges me to look at my family (who immigrated to this area during the 1860s and 1870s) and consider that they may have contributed to keeping the area very predominantly white people. According to the latest U.S. census data, Osage County is still 98.2% white. I never considered that some of my ancestors could have been racist because my mother did not raise me to engage in racist activity. I was always under the impression that since that area of the country was primarily settled by the German and French, there were not many black people living there. This is most likely not the reason behind the lack of diversity in this area. Thankfully, because I have friends who support and listen to me, I can work through my emotional discomfort and cognitive dissonance to develop a more accurate view of where I grew up. The reason the population there is comprised of nearly all white people. I do not have to engage in a false narrative to explain why there is no diversity in my home county.

Oppressive elements are present throughout teaching. It is impossible to get rid of the all; however, it is possible to constantly address ways teachers communicate unintentional lessons by examining how we teach and raising questions about it. We often do not want to talk about these questions, but most need to. To complicate the matter more, each student comes to class with their lens to view the world through. As a result, they receive messages all the time, some of which we do not mean to communicate. For example, we had two reading groups in elementary school – the “slow” reading group and the “fast” reading group. These terms reflected the speed at which each group moved through the material. It was not until I became an adult that I realized the lesson that my classmates in the “slow” group had received (and probably others in the class) because of how these groups were named. I am sure it did not help those students strengthen their reading skills and become more confident.

Buddhism may offer some insight into how to help teachers adjust their thinking/teaching to be more anti-oppressive. Socially-engaged Buddhism applies Buddhist principles to address social, political, economic, and ecological problems, so it makes sense that these ideas can also explain why relying totally on teaching knowledge does not work.

- Knowledge is binary-centered, allowing for only black and white; however, the world is full of shades of grey. By focusing on binaries, we exclude anything that does not fit into those two categories. For example, allowing only males and females excludes anyone who does not identify as one of these two genders.

- Knowledge perpetuates the belief that the world is unchanging and independent. The reality is that the world is constantly changing, and everything is interconnected. This negates that things can have different meanings in different situations to different people. It also ignores the interconnectedness of those many differences.

We cling to knowledge because it makes life feel comfortable. Humans do not like uncertainty, and knowledge provides certainty. Thich Nhat Hanh, a Vietnamese monk who teaches on socially-engaged Buddhism, believes that teaching and learning are about realizing the limitations knowledge can provide and releasing our dependence on a specific knowledge base. Knowledge improves our lives; however, we must also constantly examine how we learn and what we think to understand how it can cause us suffering. When teachers do this, they can help their students who suffer in their lives too. This is why Thich Nhat Hanh often uses the words teacher and healer as synonyms.

The author explains his type of activism: queer activism. The term queer is not used as a slur or reference to members of the LGBTQ community but rather to notate “not normal.” He wants social justice teaching to be uncomfortable to ensure that oppression and the queer are challenged constantly in our learning. We should constantly be asking ourselves, “What is problematic with the norm?” (Kumashiro pg 53). When a lesson is comfortable, doable, follow institutional practices, and is an example of “good” teaching, Kumashiro asserts that the teacher and students are not working towards anti-oppressive teaching.

He goes on to postulate that “good” teaching creates queerness, meaning that because defining something as the right or “normal” way to teach/act/be, we are creating a category where the not normal (queer) is lumped together. By constantly examining what is not normal, we bring it into the light, work through our emotions/thoughts/questions, and make it normal. Below are examples of questions that represent queer activism:

- Why does gender depend on genitalia? Why does there need to be gender at all?

- Why does gender dictate what we are allowed to wear? Why can’t people wear whatever they want regardless of gender?

Discussing these questions would produce struggle and discomfort (what the author refers to as working through crisis) in many, many people. However, by bringing these questions into the open, we can discuss the things that make people uncomfortable, hear new perspectives from others, and normalize that there is a whole gradient of gender beyond just the accepted male and female.

Part 2: Preparing Anti-Oppressive Teachers in Six Disciplines

The second section of this book applies the ideas Kumashiro explains in the first portion of the book to six disciplines. Again, he provides specifics and examples of applying anti-oppressive teaching to each subject. Below are each of the disciplines and listed significant points the author presented.

Social Studies

The author points out areas in the standard curriculum for social studies where anti-oppressive teaching can be applied. These include:

- Teach about how genocides occurred because a group of people was different or deemed “undesirable.”

- Explain/explore more about the contribution of women to the workforce during wartime.

- Discuss the relocation of Japanese American’s during World War II.

- Examine the textbook for bias in how it tells the story of history. Does it paint one group of people as the heroes? Are there groups of people excluded from the narrative?

- Discuss the actions, beliefs, look, and feel of what it means to “be an American” or “be a good citizen.”

- Explore racial and religious differences and challenging stereotypes when encountered.

- Critically analyze news stories for what is reported, how it is reported, and what is not reported.

- Question and discuss the motivations behind the actions of a government, country, or group when studying history.

English Literature

The teaching of English literature using anti-oppressive methods includes reading the classics. It works by other non-white groups to explore perspectives and experiences different from their own. Educators need to change what students read and how they read it, encouraging students to ask different questions so as not to analyze the literature from a fixed “good” perspective.

- Incorporate readings about racism in the classroom and teaching against racism illustrated in the literature.

- Read a wide range of stories from many different groups of people.

- Ask students questions that encourage them to explore the social justice topics discussed in the story and their application to the student’s own life.

- Analyze literature for the included and excluded voices/perspectives.

- Examine how different stories have different implications.

The author also indicated that teachers should not assume they know everything about their students’ experiences. They will be challenging their privilege while they teach students. Teachers need to do their homework as a result – making the teacher the student also.

Music

The study of music can be made more multi-cultural through the following anti-oppressive teaching strategies:

- Examine the historical and contextual influences present while creating a piece of music.

- Explore how different types/pieces of music allow us to express ourselves differently.

- Discuss the background of artists, groups, and cultures who created the music. How did these factors influence the music?

- List and discuss the images that come to mind during a song’s performance.

- Compare and contract emotional reactions to different styles of music.

- Discuss the hidden messages a songwriter/singer could communicate in a piece of music.

“Foreign” Languages

Learning a different language is not just about learning new words to communicate. It is also about learning about the culture and how other people operate, think, and live. It is a great way to learn about the social difference between a student’s native culture and the culture of the language studied.

Since teaching another language easily lends itself to teaching social justice, the author instead addresses his concerns about teaching another culture:

- It is easy to oversimplify a culture and thus reinforce stereotypes.

- Since it is challenging to cover all the complex nuances and details of a different culture in the average span of a classroom period, it is easy to generalize to make the lesson fit into the available time.

- Be careful to recognize the limits of the lesson to the student and identify the partial nature of the information provided.

- Focus on helping students examine the story being told about a culture critically and help them recognize this partialness.

Second, it is easy to focus on the “other” when teaching about another culture. While it is essential to teach about cultural differences, also teach about the similarities. The author states that the goal is to “change how I see and feel about others.” (Kumashiro pg 110) Focus on that during the lesson.

Natural Sciences

The natural sciences use the information to develop stories about how the world works and improve our understanding of scientific phenomenon. Framed in this context, Kumashiro encourages teachers to help their students examine these stories for any underlying information, messages, political implications, or stories not being told.

The example the author provided regarded examining the teaching of reproduction for limitations. For this particular lesson, this would include:

- Identify all forms of fertilization discussed (i.e., heterosexual, surrogateship, lab fertilization, and so forth).

- Examine how much of the fertilization and development process was taught.

- Discuss gender and the continuum of possibilities beyond just male and female.

- Analyze the social and political reasons why some of the above topics are not discussed.

- Examine the implied feminine and masculine assumptions and roles that appear in gender.

- Assess why students are open to learning about some scientific theories and law but not others.

Mathematics

While the answers to math problems may not change based on social justice issues, social factors influence math teaching. Therefore, it is essential to examine these oppressive teaching practices. Some examples of these instances are listed below:

- Problems worded to reinforce traditional racial or gender roles.

- Students can get the idea that the methods taught in the math classroom are the only or best methods when there are many other ways to approach and solve a problem.

- The theorems, formulas, and types of math taught in a classroom can be oppressive because of the context, order, or manner they are covered.

- The partial nature of math itself is not addressed in the classroom.

- Failure to connect math to a student’s real life.

It is vital to examine math’s bias and partial nature just as it is for any other subject. In addition, political, social, and cultural issues influence math, just like any of the other subjects the author discusses.

The process for developing and applying anti-oppressive teaching methods in the classroom is a career-long goal; however, it provides the critical thinking and examination skills our students need to succeed in the world. It is a significant challenge, but it is the work that will bring about changes at all levels of society.

References

K12 Academics. (2020). Anti-Oppressive Education. K12 Academics. https://www.k12academics.com/educational-philosophy/anti-oppressive-education#:~:text=Anti-oppressive education is a,challenge different forms of oppression.&text=Furthermore%2C anti-oppressive education is,that need to be challenged.).”

Kumashiro, K. (2015). Against common sense: teaching and learning toward social justice (3rd edition.). Routledge.

Kumashiro, K. (2020). Biography – Kevin Kumashiro. Kevin Kumashiro. https://www.kevinkumashiro.com/

Free Math Help. (2018). Asymptotes. Free Math Help. https://www.freemathhelp.com/asymptotes/#:~:text=An asymptote is%2C essentially%2C a,)%2C but never touches it.&text=As a result%2C the entire,it will not hit zero.)

U.S. Census Bureau. (2019) Quick Facts – Osage County, Missouri. U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/osagecountymissouri

Plum Village. (2020) https://plumvillage.org/about/thich-nhat-hanh/

Created using Canva

Created using Canva © Catherine Haslag. All rights reserved.

© Catherine Haslag. All rights reserved.